#14: When facts fail to persuade

Part 1

If we’re going to become smarter, we need to develop the skill of error-correction, that is, update our knowledge and understanding once it becomes redundant or is found to be false. The mechanisms by which this takes place aren’t fully understood, but one possible explanation is that new information is reconsolidated and assimilated into current networks of knowledge, or schemas.

However, this process doesn’t always run smoothly, and despite the addition of new information people may well cling to the old erroneous version or even reinforce it (the backfire effect, which I’ll look at in part 2). This means that providing someone with new evidence that challenges their current knowledge or belief may be rejected or suffer from biased assimilation - we distort the new evidence so that it fits better with what we already believe (a subtype of confirmation bias).

People will always hold opposing views on important issues, with each side insisting they are right. Disseminating research does take time and at least a basic understanding of the purpose and aims of research. This means we tend to rely on sources that do this for us, such as the media, writers, teachers and so-called influencers.

We can also rely on consensus, which is often much less problematic. Let’s take, as an example, climate change. Scientists are in general agreement that climate change is happening and that it’s predominately the result of human activity. This consensus ranges from 97 percent to 100 percent of active publishing scientists. In other words, pretty much every scientist on the planet is in agreement. Those scientific papers that fail to support the consensus either describe studies that cannot be replicated or contain serious errors. We can certainly describe this census as overwhelming evidence, yet there exists a significant number of people who continue to argue that anthropogenic climate change is a myth.

Why, then, when faced with overwhelming evidence, do people cling to their erroneous beliefs?

If we disregard those individuals and corporations who profit off the back of fossil fuels, or whose profits would take a nose dive if governments looked seriously into greener solutions, and focus on the general public, we’re left with a curious phenomenon: Being presented with evidence that runs counter to our beliefs should encourage us to change our minds, yet many people continue to reject the evidence and cling to these beliefs.

It might seem that the world is more polarised than ever, and this is certainly true to some extent. Misinformation is everywhere, from governments to big business - everyone seems to be doing it. According to Brendan Nyhan, a contributory factor in the rise of misinformation and ‘fake news’ is the combination of historic levels of political polarisation and advances in communication technology that has allowed false information to spread rapidly. Once in the public domain, reining in such information becomes increasingly difficult. When false information is supported by influential individuals, our ability to assimilate corrected information can become ever more problematic. Furthermore, such false information can last for months and even years.

The Curious Case of the Bendy Bananas…

One interesting example of longevity of false information concerns bananas. On a 2017 episode of BBC Question Time an audience member admitted to voting leave in the EU referendum because of straight bananas.

“I was voting remain, and at the very last minute I changed my decision and I went to leave,” the audience member said. “And the reason is because I go to a supermarket, and a banana is straight. I’m just sick of the silly rules that come out of Europe.”

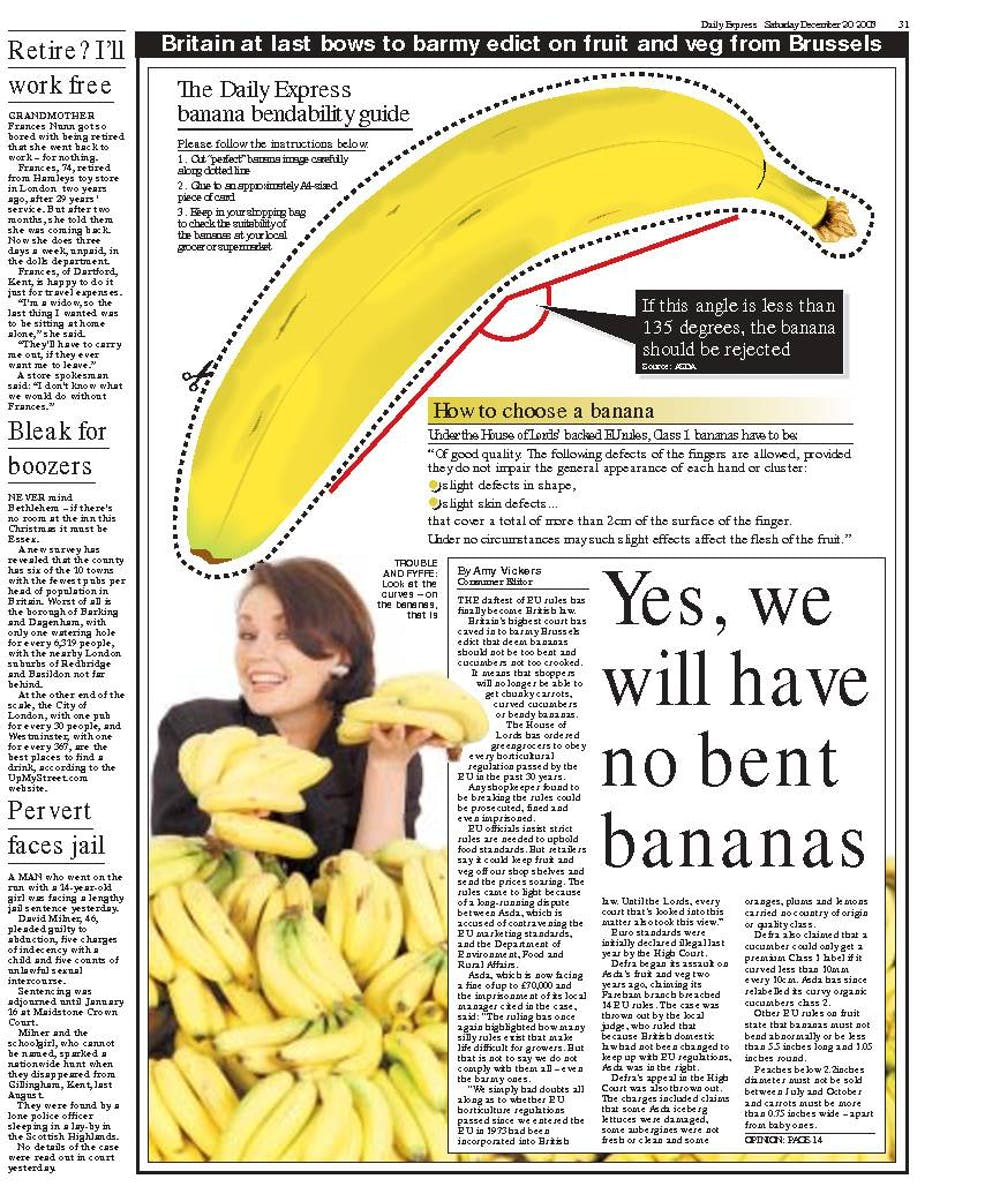

The so-called EU Banana Law myth, originated in 1994 when several UK tabloid newspapers ran stories about the EU’s attempts to ban bananas that were ‘too bendy’. Despite other newspapers running the story in more contextualised ways, the tabloid version was the one that persisted. In realty Regulation 2257/94 decrees that bananas should meet minimum quality standards such as being 'free from malformation or abnormal curvature of the fingers’, in addition, ‘bananas of the "extra" category must have no defects, but Class 1 bananas may have "slight defects of shape" and Class 2 bananas may have additional "defects of shape”.’ This is very different from stories the tabloid press ran. The Daily Express even included a handy cut out.

Then, in 2016, Boris Johnson appeared to double down on the false Banana Law story when he said it was

…absolutely crazy that the EU is telling us how powerful our vacuum cleaners have got to be, what shape our bananas have got to be, and all that kind of thing.

It seems amazing that this myth had lasted for so long, but it’s by no means surprising.

[Further reading: The Ten Best Euro Myths]

…and the Phantom WMDs

In the aftermath of the allied invasion of Iraq in 2003, the United States government concluded that the Iraqi government did not possess significant weapons of mass destruction, neither were they conducting an active WMD program (one of the primary catalysts for the war). These findings were widely publicised at the time, yet a 2015 poll found that 42 percent of Americans believed US troops found WMDs in Iraq. Interestingly, 51 percent of these identified as Republican, suggesting political affiliation can make a difference to what we believe.

Fake by accident

But false information need not be deliberate. It can also be seemingly innocuous, yet still have potentially wide-ranging consequences. Take, for example, the following paragraph looking at Cognitive Load Theory from the Education Endowment Foundation’s 2021 report on cognitive science in schools.

Educational psychologists and cognitive scientists make the distinction between (1) intrinsic load on the working memory, determined by the nature of the information to be learnt (for example, the difficulty of a task), (2) extraneous load, which is caused by unnecessary or distracting information that is not essential the learning of the target information, and (3) germane load, the load specifically used for developing knowledge (via the construction or alteration of schemas) in the long-term memory (p.93-94)

The false information here is subtle and unlikely to be deliberate. Many, if not most, cognitive scientists don’t make the distinction claimed, because they don’t operate within a Cognitive Load Theory paradigm - most don’t make any distinction between types of load, it’s all just load. The underlying implication here is the Cognitive Load Theory has been endorsed by all (or at least most) educational and cognitive psychologists, a claim that simply isn’t true.

A second issue is that germane load has all but disappeared from the literature. Indeed, in his introduction to Advances in Cognitive Load Theory from 2020, John Sweller makes no reference to it at all, although other contributors to the book do. Like I said, these errors are subtle. The second one is perhaps less problematic than the first; theories adapt and change and it’s not always easy to keep up. The first error, however, has potentially wider consequences, because it implies consensus amongst educational and cognitive psychologists.

It also implicitly conflates cognitive load with Cognitive Load Theory, which simply exacerbates this common error and stifles understanding (I have a post here that looks into cognitive load in a little more depth).

Schemas can lead us astray

If new information requires assimilating into schemas, can our beliefs lead to biased assimilation?

Jason Coronel and his co-researchers from Ohio State University set out to test how schemas can lead people to misremember factual information. They were interested in how people recalled numerical information if the data ran counter to their own internal schemas. The researchers presented participants with short written descriptions of four societal issues involving numerical information. On two of the issues, they ran a pre-test to discover the relationship between the issue and the participants' understanding of it. For example, they were presented with information that most Americans supported same-sex marriage than opposed it and participants agreed that this was, indeed, the case. In other words, the data was schema-consistent.

But they also presented volunteers with data that were schema-inconsistent. For example, most people in the US (according to polls) believe that Mexican immigration into the country increased between 2007 and 2014 when, in fact, it declined from 12.8 million to 11.7million (their belief ran counter to objective facts). After being presented with the statements, participants were given a surprise recall test (they were not told in advance to remember the information).

Generally, participants were pretty accurate in their recall of the data, however, on the schema-inconsistent information there was a tendency to reverse the numbers. Rather than remembering that Mexican immigration fell from 12.8 million to 11.7 million, they recalled that it had risen from 11.7million to 12.8 million.

Maybe they simply weren’t paying attention when they read the information? Information that violates people’s schemas should attract greater attention than information that is schema consistent, so we should be more accurate with schema-inconsistent information. To investigate this, the researchers used eye-tracking technology to see if participants were focussing more on the information that ran counter to their schema. Sure enough, the volunteers spent more time reading the schema-inconsistent information, their eyes continually flicking from one section to another, presumably in an attempt to reconcile the contradictory data. However, despite greater attention, their ability to remember the information correctly was still compromised.

This would imply that the errors were less to do with attention and more to do with misremembering. Participants were recalling the gist of the information, but to maintain consistency with their own mental models (their schemas) they misremembered the position of the data. Their desire for consistency was more powerful than the desire to be accurate. Schemas, therefore, can also lead us to misremember.

How likely, therefore, are we to change our minds when presented with evidence? It perhaps depends on our current beliefs and how embedded they are, but it also appears to be related to who provides the evidence and how forceful they are. An area I’ll discuss in part 2.